Random beauty: The surrealist in the machine

I wrote software to generate compositions that resemble the photomontage style of early 20th century surrealists. Developing it led me to think about the ways in which randomness has been harnessed as a productive creative force, and how computers are a powerful amplification of that force.

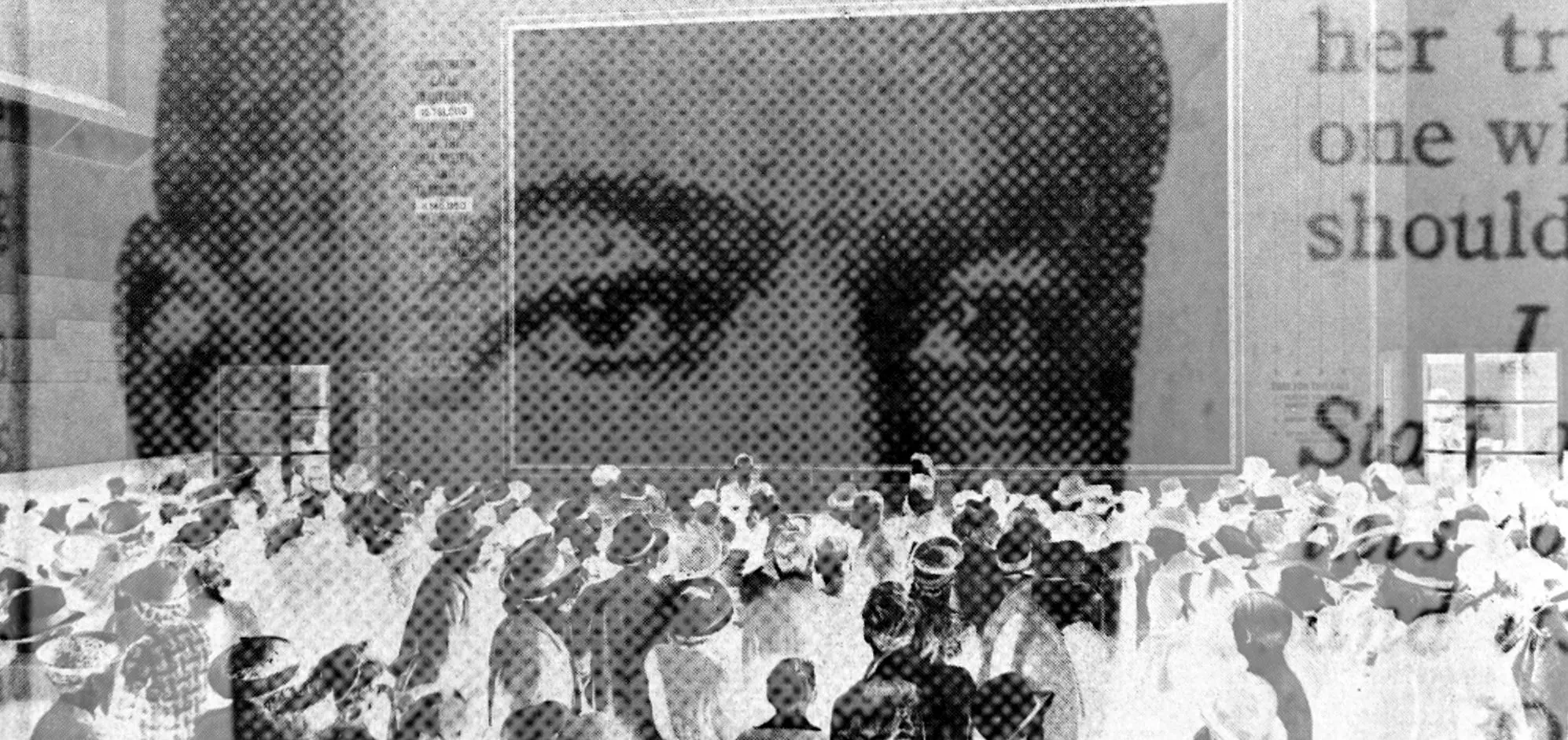

In December 2015 I visited an exhibit of early experimental photography at the Museum of Modern Art. I was particularly taken with the photomontages—composites of layered images that were alternately haunting, beautiful, or charmingly pretentious.

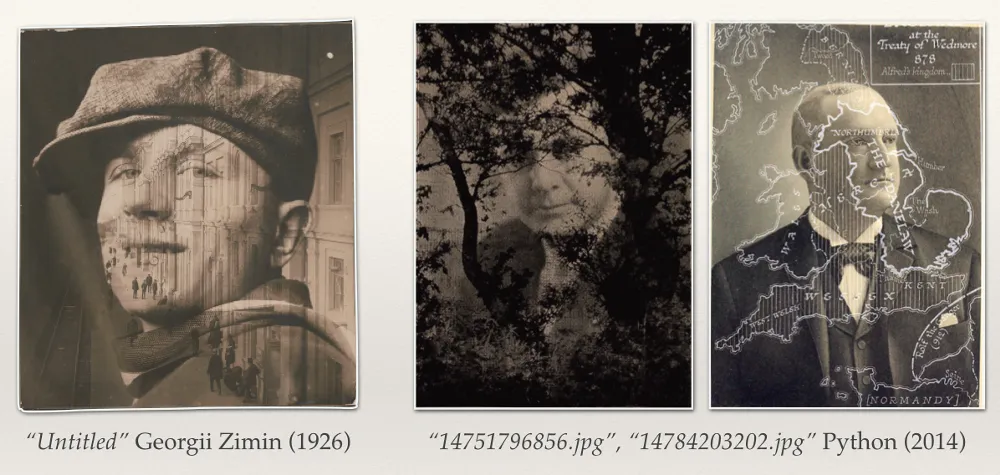

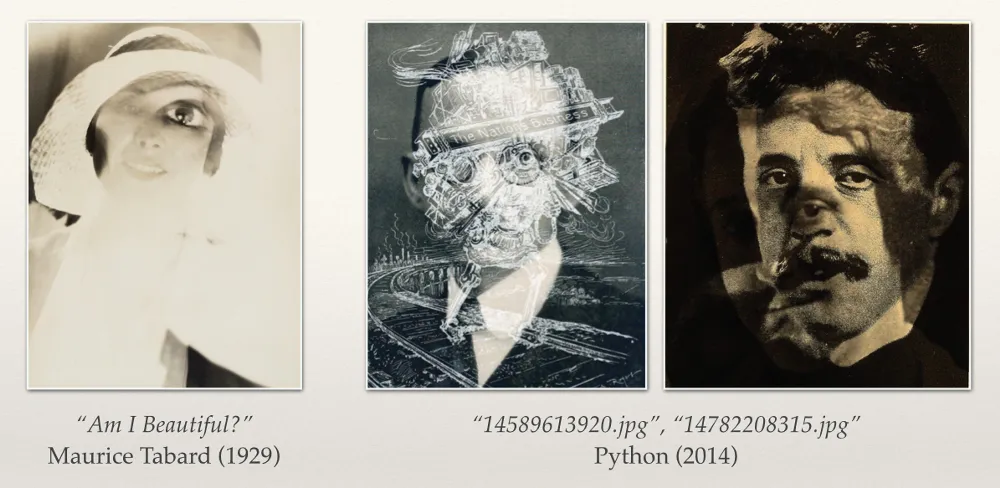

I returned home with an inspiration: get a computer to make more of them. After a few nights and weekends I had my program: a Python script that can churn out thousands of ersatz avant-garde photomontages in an hour.

It’s not “computer-generated art”. The source material, random images extracted from public domain books, were all made by humans, and some of those humans were artists. The computer is just culturally appropriating us.

To create is divine, to reproduce is human.

—Man Ray, “Originals Graphics Multiples” (1973)

I’ve concluded that the program is Dada—lacking in meaning, anti-art, assembled from “readymades” but that the work is Surrealist — strange, surprising, heavily random, but not total visual noise. Dada employed randomness as an expression of nihilism, a metaphor for merciless modern war and economic injustice. My software isn’t a person and doesn’t do metaphors. It can’t help but produce imagery that’s intrinsically meaningless.

The work is the subset of that imagery that, as a human, I decided signified something. It might signify comedy or tragedy or synchronicity; it might amuse us or unsettle us; it might be strangely beautiful or just strange. I pulled each image out of the slush pile for a reason. Randomness is only a creative input to the project, not its reason for existing. That makes it Surrealist.

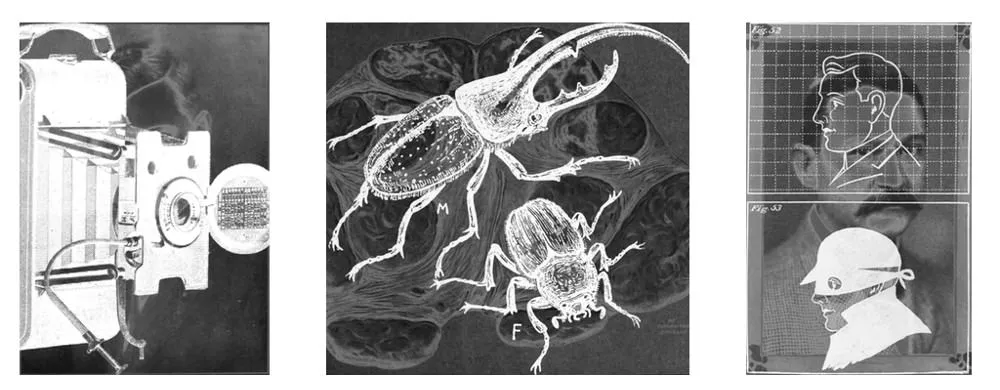

Blending images was a technique used by many different artists of the early avant-garde. As is often true for new forms of expression, artists wanted to show off the process itself. Early collages were ragged, literally cut and paste, with visible seams between the composite images. They looked like what they were: distinct visual elements glued together on a page.

The Surrealists preferred softer photomontages achieved in the darkroom. Their process would produce a single image which, while obviously a composite, felt stylistically whole. The desired look was dreamlike, sensuous.

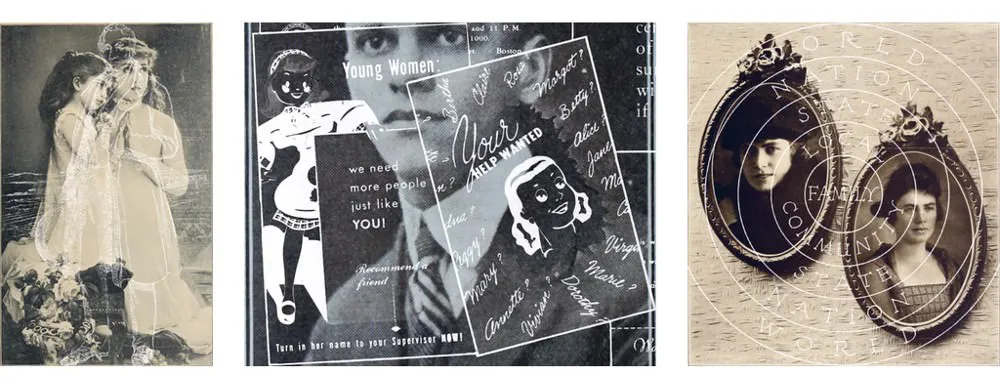

One of the few “aesthetic” judgments that my program makes is to prefer combinations of images that are computationally different enough to be interesting. My favorites tend to be visually harmonious, in line with Surrealist principles, but thematically contrasting: a dainty illustration blended with an artifact from an old book, or an angelic panel of women swallowed by a machine.

I am particularly struck by the computer-generated compositions that include women. Whatever they are randomly juxtaposed with tends to feel layered with meaning.

For all their modernist drive, the human Surrealists—Breton, Man Ray, Duchamp—were men of their time. Metaphorical women represented beauty, to be admired or ravaged to induce shock. Real women were useful lovers, assistants, companions. In one sentence of “Manifesto of Surrealism” André Breton name-drops more than twenty men who hang around his salon: “Georges Malkine, Antonin Artaud, Francis Gérard, Pierre Naville, J.-A. Boiffard.” Lest you get the wrong idea, he concludes: “and gorgeous women.” He does not name them.

One of the unnamed was Claud Cahun, who orbited in Breton’s circle yet was never fully accepted. She presented as a lesbian but her gender identity was mercurial: “Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.” She had drifted away from the core Surrealists by the time the Second World War erupted and fled to the British island of Jersey with her partner. The pair of them recklessly but anonymously blanketed the island with anti-Fascist propaganda—for four years!—before they were caught and sentenced to death. Their execution was indefinitely deferred in part because her captors could not accept that they had no male co-conspirators. “They were forced,” Cahun wrote, “at the end of the day, to condemn us without believing in our existence.” Cahun’s work was difficult, disturbing, and is mostly lost, due to outright destruction by the Nazis but also indifference. Until very recently she was virtually unknown.

Surrealists were fascinated by the eye. They obsessed over its aesthetic beauty and employed it as a metaphor for the unconscious. “The eye exists in its savage state,” André Breton wrote, believing that the sense of sight was immediate, unsullied by rationality, and therefore the purest entryway to the true self.

I don’t believe in the unconscious in the same way, but eyes are striking. They’re so stereotypically “Surrealist” that I found myself gravitating towards any composition that emphasized them.

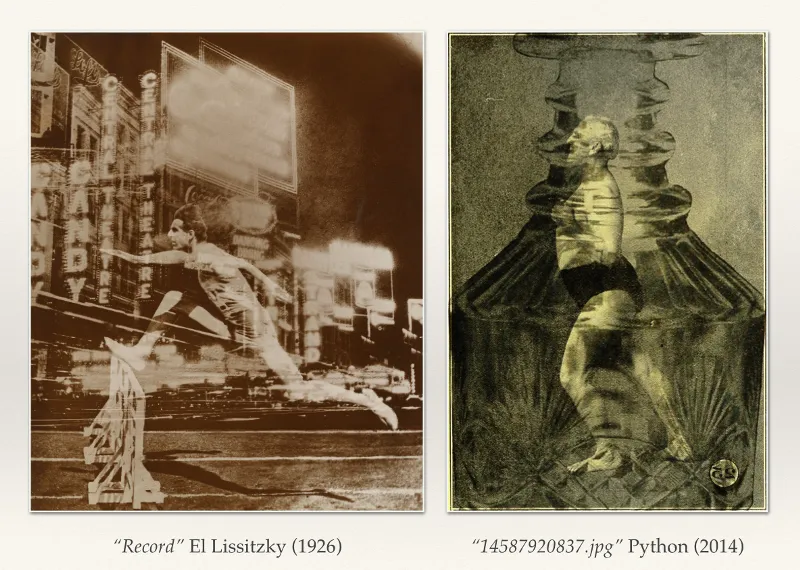

Neither of the artists above took the photos that make up these compositions. Lissitzky didn’t photograph the street montage (that’s an uncredited Broadway bei Nacht by Knud Lönberg-Holm). The source of the runner is unknown. Python’s composition is not real art but it’s funnier and has a better excuse for not crediting its sources.

The Surrealist atmosphere created by automatic writing, which I’ve wanted to put within everyone’s reach, is especially conducive to the production of the most beautiful images.

—Breton, Manifesto of Surrealism (1926)

Breton claimed to believe in “objective chance” —that seemingly random events would reveal themselves to be predestined expressions of human desire. One morning you would be drawn to a strange object in a flea market; weeks later you would realize you needed that exact thing. The specific theory of objective chance died with Breton, but the loosely defined concept persists. It’s recapitulated in formal theories like Jung’s synchronicity and really disappointing movies like Signs.

To learn anything requires close observation of a noisy world and the ability to extract patterns from it. As humans we’re evolutionarily predisposed to find meaning in random signal. Breton and Jung had the causality of chance backward, and while that makes them wrong, it doesn’t make them foolish. Even the most rational among us have experienced seemingly magical coincidences that we stubbornly hope have some underlying narrative.

One of the things I love about projects that use randomness, whether they’re twitter bots or computer-generated literature or just analog Surrealist party games, is that they force to admit that sometimes interesting things just happen. Objective chance is an unnecessary adornment on a wonderful aspect of life. Any one of us, no matter how ugly, untalented, unloved, or unhuman, might—by random chance—create something beautiful.

A complete photoset of the works are on Flickr.

The source code and the images are in the public domain.

Some parts of this were first presented at the Boston Python User Group in 2015.

All unattributed works in this story are by Python.